Uveitis

A rare, potentially chronic and blinding, inflammatory disease of the eye.

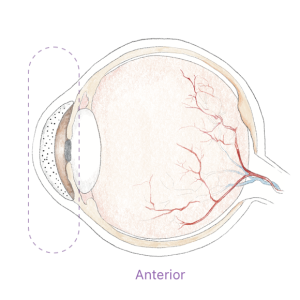

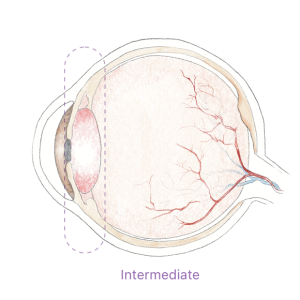

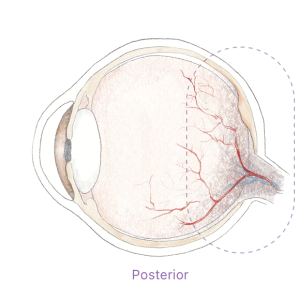

Uveitis can be classified as infectious (resulting from bacteria or virus) or non-infectious (autoimmune, idiopathic cause). Uveitis can occur in one or both eyes of a patient, in different segments of the eye

Uveitis can be anterior, intermediate, or posterior. The inflammation can be present in both eyes at the same time, affect one eye, or alternate from one eye to the other.

~700,000

Patients in the U.S.

with different types of uveitis

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with uveitis may experience pain, light sensitivity/photophobia, eye redness, decreased vision, blurred vision, or “floaters”.

If not treated properly and promptly, uveitic flare-ups may lead to blindness.

Uveitis & Blindness

10%-15%

of blindness in the U.S.

is due to uveitis

Non infectious anterior uveitis

The most common form of uveitis

The cause is often unknown and is said to be autoimmune. In these cases, an inflammatory response in the eye arises even without a well-defined stimulus. The ocular inflammation is initiated by inflammatory macrophages that secret inflammatory cytokines. This leads to a cascade of events that eventually ends up in immune cells entering the anterior chamber of the eye, which is otherwise an ‘immune privileged’ site.

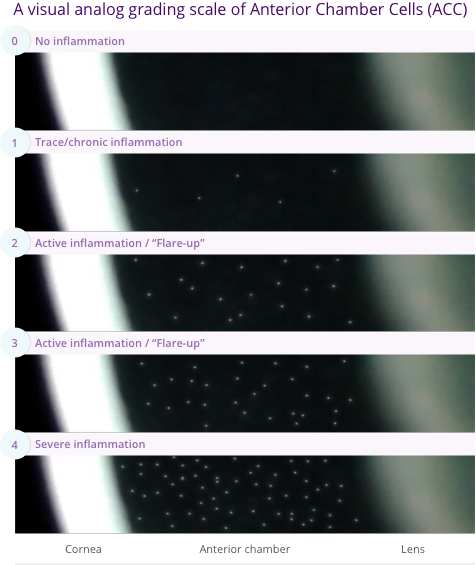

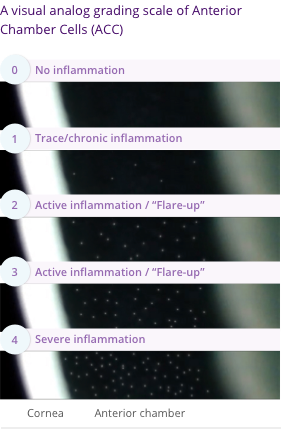

The main hallmark of non-infectious anterior uveitis is the presence of immune cells floating inside the anterior chamber of the eye, and the severity of the uveitis can be determined by the quantity of cells present, seen in a slit lamp examination.

A visual analog grading scale of Anterior Chamber Cells (ACC)

Is non infectious uveitis treatable?

With available treatment options, visual loss occurs in about two-thirds of uveitis patients, with 22% of patients meeting the criteria for legal blindness at some point of their follow-up.

Existing treatments often start with topical steroids, followed by systemic immunosuppressants (such as biologics, T-cell inhibitors, alkylating agents etc).

Steroid eyedrops are potent at resolving inflammation, but prolonged use entails severe and blinding side effects (i.e., glaucoma, intraocular pressure elevation, formation of cataracts etc.).

Immunosuppressants are prescribed to provide a long-term reduction of the number of attacks or prevent them altogether.

Their use requires more clinic visits to monitor their effect and avoid side effects including infections, diabetes, and in some cases cancer. As a result of serious safety concerns, many systemic immunosuppressive drugs are not approved for pediatric use.

Recurrent exacerbations of uveitis can lead to cumulative damage and cause tissue destruction and scarring, and a variety of complications, such as retinal swelling (macular edema), retina scarring, glaucoma, cataracts, optic nerve damage, retinal detachment, low eye pressure (hypotony) and eventually in some cases, permanent vision loss.

immunosuppressive treatment requires 2-12 weeks to take effect. As a result, topical steroids still remain the only available treatment for a new flare-up or active disease.